The Evolution of the Right-Wing Attacks on ESG

An investigation reveals how a web of political operatives with ties to Leonard Leo are blocking financial institutions from assessing climate risks.

An investigation reveals how a web of political operatives with ties to Leonard Leo are blocking financial institutions from assessing climate risks.

Internal documents show how corporations have co-opted the quasi-governmental body to push for deregulation of the industry.

A trove of internal NAPCOR documents offers an in-depth look inside a multiyear covert campaign to convince Americans single-use bottles are sustainable.

Shortly before his nomination, Lee Zeldin was enlisted in a stealth lobbying campaign against a right-wing threat to BlackRock’s bottom line.

Documents obtained by Fieldnotes and first reported on by Canary Media detail a coordinated and comprehensive effort by some of the largest oil & gas companies in the United States to pressure Ohio lawmakers to clear the way for the corporations to profit from carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the state.

The effort, which lays the groundwork to transfer oversight of CCS projects in Ohio from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to state regulators—most likely speeding approval and weakening environmental protections—is being led by the American Petroleum Institute (API) and the Ohio Oil & Gas Association (OOGA). Together, the trade groups represent a wide swath of oil & gas power players, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, ConocoPhillips, Occidental Petroleum, Energy Transfer, and Halliburton.

Communications obtained via public records requests show API and OOGA working on several fronts to orchestrate passage of legislation needed to give Ohio the authority to regulate CCS wells. The documents show the trade groups drafting the bill in question; hand-picking state lawmakers to introduce it; lining up witnesses to testify in support of it; providing lawmakers with talking points and other materials to advocate for it; and offering to coordinate “earned media opportunities” as part of a press strategy to amplify their message.

Throughout the process, API and OOGA have been in regular contact with their chosen lawmakers. Records show they have met with the bill’s sponsors in person or on Zoom on at least a dozen separate occasions since late 2023, and exchanged more than a hundred emails with the sponsors’ staff during that time. The lobbying blitz has not been confined to normal work hours or settings, either. This past January, for example, API organized a white tablecloth dinner for one of the sponsors and a handful of executives from its member companies.

The legislative push remains ongoing. The Ohio legislature held four committee hearings on the bill during the first half of this year, and the Republican majority in each chamber could bring the bill to the floor as soon as this September when lawmakers return from summer recess.

API, OOGA, and the state lawmakers who sponsored the CCS legislation did not respond to a list of emailed questions from Fieldnotes about the groups' involvement in the legislative process. In a statement to Canary Media, Christina Polesovsky, an associate director in API’s Ohio office, said that her group “regularly engages with policy makers on both sides of the aisle to educate on the critical role of American energy and to share our industry’s priorities.”

“Carbon capture has become… the new wild west, the new Spindletop in Texas, the new Colonel Drake well in Pennsylvania, where there is a lot of money to be made.” Jennifer Stewart, API director of climate and ESG policy

Under pressure to address the industry’s role in the climate crisis, many oil & gas companies have in recent years embraced CCS as a way to maintain their social license without actually curtailing production—and to make money in the process. The industry has successfully lobbied the federal government to back the technology by funding R&D and subsidizing projects through tax credits. In 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act set aside $12.1 billion for CCS development, and in 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act boosted the main CCS tax credit (known technically as 45Q) from $50 per metric ton to $85 for CO2 that is captured from point sources, like ethanol plants, and sequestered underground. (The recent reconciliation bill left the CCS tax credits in place, but added foreign-entity-of-concern requirements.)

To put it more plainly: After spending the past century making a fortune pumping carbon out of the ground, the oil & gas industry is now hoping to make a fortune pumping carbon back into the ground. Companies are so excited about the financial potential that API has talked about CCS in the same breath as some of the industry's most lucrative milestones. As Jennifer Stewart, API’s director of climate and ESG policy, put it during a spring 2024 Ohio Senate committee hearing: “Carbon capture has become… the new wild west, the new Spindletop in Texas, the new Colonel Drake well in Pennsylvania, where there is a lot of money to be made.”

But before industry can start making money, there’s one problem: permitting. Right now, only four states—North Dakota, Wyoming, Louisiana, and West Virginia—have what is called “primacy" over CCS wells, which are classified as Class VI injection wells under the Safe Drinking Water Act. In states with primacy, state regulators can grant permits. In states without primacy, companies must apply for permits through the EPA, where the wait time is two-plus years.

Industry would prefer to work with states, as opposed to the EPA, because it’s typically faster and cheaper to get a state permit. To that end, API is pushing states to apply for Class VI primacy, and many are heeding the call. Roughly 20, including Ohio, have passed or proposed the legislation required to formally request the EPA grant them the authority to green-light CCS projects.

Easing the ultimate path to primacy is President Trump’s EPA. In May of this year, an EPA official told oil & gas regulators that Administrator Lee Zeldin has directed staff to “fast-track” states’ Class VI primacy applications. The agency, the official added, is actively looking for “opportunities to shave off components of that process to make sure that we’re moving things forward as quickly as we can.”

“We’re gonna operate this for 25 years. I don’t want it to be on my books indefinitely as a liability. How do we transfer that liability over to the state, much in the way that somewhat happens through a plug and abandonment program?” API Gulf Coast Regional Director Gifford Briggs

An industry-designed CCS regime offers oil & gas companies the chance to not only make money from carbon capture projects—but also to save money by handing off their eventual cleanup responsibilities to taxpayers. That’s because most state CCS laws, including the one proposed in Ohio, contain liability transfer provisions, which shift the financial liability for CCS projects from private corporations to state governments after a certain number of years or after certain conditions have been met.

The idea is that companies pay into a state trust fund for each ton of CO2 they inject into the ground. Then, after the state assumes liability for the CCS project, it uses the trust fund to pay for monitoring and remediation. But what happens if the trust fund doesn’t cover all the expenses? The state is left holding the bag.

These provisions are explicitly modeled on the frameworks that states use to manage orphaned and abandoned wells, which have allowed oil & gas companies to walk away from their responsibilities and transfer more than $150 billion in cleanup costs to taxpayers.

Here’s what often happens under those frameworks: Companies are legally required to plug their wells once they stop producing, but sometimes they go bankrupt or are otherwise unable to fulfill these responsibilities, leaving the wells “orphaned.” When this happens, states have to plug the wells to prevent them from leaking contaminants into the air, ground, and water. States require oil & gas companies to post bonds to help cover potential cleanup costs, but these bonds are woefully inadequate. Ohio, for example, requires just a $15,000 blanket bond to cover an unlimited number of wells, yet it costs the state an average of $78,774 to plug a single one, according to the Ohio River Valley Institute. (The state also generates funds for orphaned-well plugging through a severance tax on oil & gas production, but it’s not enough; Ohio has more than 20,000 known orphaned wells, according to a 2024 report.)

Instead of plugging their wells, an oil & gas company often sells those that are nearing the end of their lives to a smaller company, which then sells them to an even smaller company, and so on down the line until the final owner goes bankrupt and dumps the cleanup costs onto taxpayers. This series of events is so common, those who track it closely have dubbed it “the playbook.” States could update their laws to prevent it, but the oil & gas industry has resisted reform efforts across the country.

If state laws similarly allow private corporations to transfer liability for CCS projects to the state, it’s easy to see how taxpayers could once again be on the hook for cleaning up industry’s mess.

The Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC)—a quasi-governmental agency made up of state regulators and oil & gas industry representatives—laid the groundwork for liability provisions in state CCS laws back in 2007. More recently, API Gulf Coast Regional Director Gifford Briggs underscored the corporate logic at an industry conference last year, summing up oil & gas companies’ thinking like so: “We’re gonna operate this for 25 years. I don’t want it to be on my books indefinitely as a liability. How do we transfer that liability over to the state, much in the way that somewhat happens through a plug and abandonment program?”

“The real problem is that the communities that are impacted by the activity of these organizations’ wells have a very minimal presence and limited input. And it’s not for lack of trying.” Ohio State Rep. Tristan Rader (D)

Communications between API, OOGA, and Ohio officials make clear that the oil & gas industry is driving the effort to pass a CCS law there. The effort began in earnest in 2023, when an API lobbyist invited senior staffers working for Gov. Mike DeWine to a CCS briefing co-led by Shell and the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

A few months later, API and OOGA went looking for Ohio lawmakers to carry out their CSS plan. On the recommendation of House Republican senior staffers, API selected Rep. Monica Robb Blasdel, who they vetted with other industry allies. And on the Senate side, API successfully convinced GOP Sens. Tim Schaffer and Al Landis to sign on to the effort. In December 2023, Robb Blasdel, Schaffer, and Landis introduced one-page placeholder bills declaring their intent to regulate CCS.

Meanwhile, API and OOGA also began working with Ohio DNR. In November 2023, API's Christina Polesovsky sent a draft bill to Ohio’s chief oil & gas regulator. “Please find the draft bill OOGA and API Ohio have compiled with feedback from our members and technical consultants,” she wrote. “We thought it might be helpful to walk you through the bill, the process we’ve undertaken in crafting the draft, and the strategy we are taking as it relates to CCS in Ohio.”

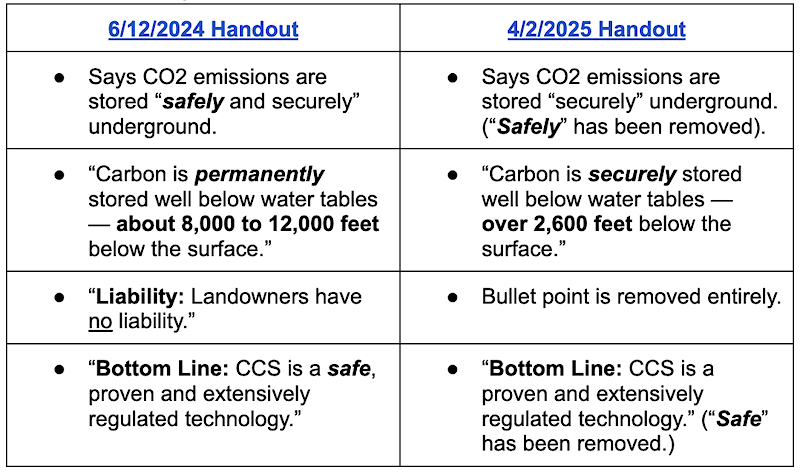

API and OOGA continued to shepherd their bill as it moved through both chambers in 2024. When a committee chair asked Landis’ office if the senator wanted to do sponsor testimony, his aide deferred to API, asking Polesovsky “if we’re ready to do sponsor testimony or if you guys are still getting the final pieces of the full legislation.” When the Senate and House committees eventually held hearings on the bill, API lined up the expert witnesses who testified in support, and provided related handouts to lawmakers.

Likewise, when the Legislative Service Commission (LSC), a nonpartisan agency tasked with analyzing legislation for lawmakers, had questions about a substitute bill, aides again turned around and forwarded those questions to API and OOGA. And when the LSC ultimately recommended changes, aides sent those changes to the lobbying groups for feedback.

Emails from API’s Polesovsky show that every new iteration of the bill has been written or carefully reviewed by oil & gas companies. In a March 2024 email to CCS stakeholders, she wrote, “The collective industry … will convene this Friday to further refine our draft bill for consideration by the members of API Ohio and OOGA. Once the industry has reached consensus, we will share with this group.” A month later, Polesovsky updated the Senate sponsors’ aides: “Once we have a new revised draft from LSC we will distribute to our collective membership for sign off and at that point we will have language for a substitute bill to begin the public discussion.” Later, when API passed along edits from Encino Energy, the largest oil producer in Ohio, legislative aides incorporated the corporate edits verbatim.

Despite those efforts, the industry-backed CCS bill stalled in committee in 2024. This year, however, the push continues. API’s allies have re-introduced an updated version in both chambers. Rep. Bob Peterson—whose district includes a Valero ethanol plant with a financial interest in CCS—joined Robb Blasdel as a co-sponsor in the House, while Sen. Brian Chavez replaced Sen. Landis as a co-sponsor in the Senate.

The oil & gas industry has continued to enjoy extraordinary access to these lawmakers as they push their bill toward the finish line. For example, executives from API and some of the group’s member companies dined with Chavez at a white tablecloth restaurant in January. Chavez similarly discussed the CCS legislation over dinner at another upscale restaurant with executives from Tenaska—a company pursuing its own CCS project spanning 80,000 acres in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—in March. Later that same month, Chavez and his cosponsors introduced the latest version of API’s CCS bill.

“The real problem is that the communities that are impacted by the activity of these organizations’ wells have a very minimal presence and limited input,” Rep. Tristan Rader, a Democrat who says he hasn't yet decided whether he supports the CCS bill, told Canary. “And it’s not for lack of trying.”

Emails, calendar invites, and other records obtained by Fieldnotes show API and OOGA working on multiple fronts to orchestrate passage of CSS legislation in Ohio. The industry groups have met with the bill’s sponsors in person or virtually on at least a dozen occasions since late 2023, and exchanged more than a hundred emails with the sponsors’ staff during that time. They also drafted the bill in question, found lawmakers to introduce it, and lined up witnesses to testify in support.

2023

2024

(2) Primary responsibility and liability for the stored or injected carbon dioxide shall be transferred to the state… except under any of the following circumstances:

(b) After notice and a hearing, the chief determines either of the following:

(ii) There is carbon dioxide migration that threatens public health or safety or the environment of underground sources of drinking water.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy